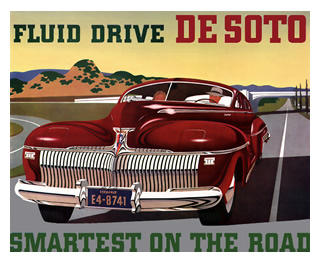

All Classic Ads Vintage Collection - DeSoto related ads All Classic Ads Vintage Collection - DeSoto related ads

Ad • Ad

|

|

History of DeSoto (1928)

Walter P. Chrysler introduced DeSoto in the summer of 1928.

Chrysler's announcement immediately attracted 500 dealers. By the time DeSoto production was in full swing at the end of 1928, there were 1,500 agencies selling the premier 1929 DeSoto Six. Demand rocketed.

During the first twelve months, DeSoto production set a record 81,065 cars. DeSoto built more cars during its first year than had Chrysler, Pontiac, or Graham-Paige. The record stood for nearly thirty years.

The car name honored Hernando de Soto, the 16th century Spaniard who discovered the Mississippi River and had covered more North American territory than any other early explorer (editor’s note: the Chrysler people were probably not aware that DeSoto was a brutally ruthless conquerer, leading to the murder of thousands of people, as well). As a moniker, DeSoto reinforced the Americana theme sounded by Chrysler's other new brand, Plymouth; towns, cities, and counties named DeSoto are spread across the southeastern United States

The car itself was a mid-price, six cylinder, 55 horsepower bargain. DeSoto provided engineering advantages such as an oil filter and Lockheed hydraulic brakes that were either optional or not offered by contemporary makes. DeSoto niceties included standard automatic windshield wiper, ignition lock, brake light, full-instrumentation, steering hub controls for headlights, and a tool kit with grease gun.

It was a smooth package made more appealing by seven different models with swank names. The roadster was called Roadster Espanol. The deluxe sedan was called Sedan de Lujo. Even the basic two-door benefited as the Cupe Business.

DeSoto returned for 1930 with even more. At the top of the line was the DeSoto CF, otherwise known as the DeSoto Eight.

Here was a bigger DeSoto with a 114 inch wheelbase and the kind of inline eight cylinder engine customers expected to see in a luxury car. DeSoto called it "the world's lowest-priced straight eight" and promised customers "a vast reserve of power when you need it." With 70 horse power and 207.7 cubic inches, the DeSoto Eight delivered.

Even though 1930 was the first full year of the Great Depression, the DeSoto Eight accounted for 20,075 DeSotos built.

How Chrysler Corporation

in general and DeSoto Division in particular responded to the Depression is exemplary. Product development continued unabated, and the mood was still Jazz Age bright.

DeSoto kept the public engaged by performing spectacular feats of speed and stamina. In 1932, race car driver Peter DePalo sped across the United States in ten days at the wheel of a DeSoto. When his journey ended, DePalo took his DeSoto for a 300 mile race-track spin hitting speeds as high as 80 miles per hour.

In 1933, DeSoto recruited another race car driver for a more astounding publicity stunt. This time, Harry Hartz drove a DeSoto backwards across the country. Hartz peered his way across the continent through a rear window turned windshield.

Spectators couldn't know it at the time, but the Hartz trip was the first public manifestation of top-secret experiments brewing in the engineering laboratories of Chrysler Corporation. The results of those experiments would change the world.

Airflow and Airstream

Wind tunnel testing began in 1927. Chrysler engineers discovered that contemporary automobiles moved more efficiently through the air with the body reversed. Hence the "backwards" DeSoto Hartz drove. The revelation prompted an ambitious quest for the ideal aerodynamic body that would save gasoline and increase speed. The search would inspire a fundamental re-evaluation of car design, and bring true modernity to motoring.

The result was the 1934 DeSoto Airflow, DeSoto's boldest adventure. "Goodbye Horseless Carriage," shouted DeSoto advertising, "Here's the New Airflow DeSoto!"

Airflow styling said, "Woosh!" Blown away were free-standing headlights, radiator shells, side-mounted spare tires, and bobbed tails. In their place was a svelte, envelope body whose lines slithered fore and aft in a relaxed arch. Most radical was the front, whose waterfall grille simply let the wind pass so that the car may go faster.

Sleekness was only part of the package. The DeSoto Airflow concealed a revolutionary chassis with the interior moved 20 inches forward. Correspondingly, the engine compartment was placed between rather than behind the front wheels. Not only did this new configuration cradle passengers within the wheelbase, but it reversed traditional weight distribution for a front end bias, eliminating fore and aft pitching and reducing rebound motion by 20%. The result was a smooth "amidships ride."

It's an arrangement most new cars have followed ever since.

DeSoto promotions liked to say that an Airflow passenger could comfortably read his newspaper while the driver navigated a dirt road at 80 mph. DeSoto was so confident of Airflow's on-road stability that hand straps were purposefully eliminated from the cabin.

The interior was among the most luxurious and safest in the world. Beautifully upholstered seats set in chrome frames offered the industry's first comfortable six passenger capacity. Ventilation was outstanding due to airspace beneath the front seats, elaborate dual action windows in the front doors, twin cowl vents and crank out windshields. Being cool and comfortable meant the Airflow driver could better appreciate the ergonomically angled steering wheel that allowed shoulders to relax.

Airflow design propelled DeSoto to 32 stock car records. Airflow scorched the flying mile at 86.2 miles per hour, averaged 80.9 miles per hour for 100 miles, 76.2 miles per hour for 500 miles, and 74.7 miles per hour for 2,000 miles. For gravy, Harry Hartz drove a DeSoto Airflow 3,114 miles from New York to San Francisco. The DeSoto averaged 21.4mpg, with a total gas bill of $33.06.

With the Airflow, Walter Chrysler made the cover of Time. The January 8, 1934 issue captioned the industrialist's portrait with the catchy line, "He made the buggy a bugaboo." Inside, a curiously staged interview asked Mr. Chrysler of the Airflow, "Do you think the public is ready for anything so radical?" Mr. Chrysler responded, "I know the public is always ready for what it wants... and the public is always able to recognize genuine improvement." True, the public did recognize that the DeSoto Airflow was a genuine improvement - in Europe.

The DeSoto Airflow was a hit overseas. The Monte Carlo Concours d'Elegence presented DeSoto with the Grand Prix award for aerodynamic styling. European manufacturers such as Peugeot, Renault, and Volvo went so far as to copy the Airflow look for their production cars.

More remarkable is that in distant Japan the first mass produced Toyota was styled to resemble the 1934 DeSoto.

DeSoto promoted the Airflow hard at the 1934 "Century of Progress" World's Fair in Chicago. Babe Ruth, Dick Powell, Ruby Keeler and Ethyl Merman all made various celebrity appearances on behalf of the car, too. The American driver, however, wasn't buying.

1934 DeSoto deliveries declined 47% and only 13,940 Airflows were built for the model year. DeSoto fell from 10th to 13th place in the industry.

One Airflow brochure called style a state of mind. Clearly, customers were thinking of something else.

DeSoto acquiesced to the public's dislike for the Airflow and fielded a conventionally styled and engineered Airstream companion series for 1935. Each succeeding model year, the Airflow itself wore a more pronounced art-deco nose trying to disguise its unorthodox profile. In 1936, the Airflow line was canceled.

DeSoto's conservative turn was rewarded. Sales nearly doubled for 1935 thanks to enthusiasm for the Airstream, its replacement. DeSoto was given its own production facilities in 1936 and sales climbed again by more than ten thousand cars. On the strength of a handsome 1937 re-styling, production more than doubled to 81,775, moving DeSoto from 13th to 12th in the industry. For the first time since 1933, DeSoto outsold Nash.

Hollywood Style DeSoto - 1939

By 1939 DeSoto was ten years old and a new member of the industrial establishment. Parent company Chrysler Corporation was now the second largest automobile manufacturer in the United States, perhaps the world. Chrysler had won the position thanks in large part to the strength of its mid-priced cars like DeSoto. Time had come to flaunt the spoils.

"The extent of design changes and improvements in the 1939 DeSoto," said a 1939 press release, "indicated the lengths to which the Chrysler Corporation has gone to stimulate new car buying. As a part of Chrysler Corporation's $15,000,000 program for new dies and retooling of the 1939 models, several million dollars were spent on the new DeSoto body alone."

Maybe that's why DeSoto called the new look Hollywood Style.

"Ginger Rogers," claimed one DeSoto advertisement, "drives Hollywood's smartest car - DeSoto!" "I like action!" Ginger supposedly said. "I get it in my DeSoto."

Ginger didn't need any help, but the 1939 DeSoto was a looker. Those slippery curves that had made the Airflow distinctive were back with a new finesse. Sedans were fastbacks. All models featured curvaceous fenders blown taught by an unfelt wind. Up front was a tall prow suitable for an ocean liner, and enough chrome to blind on-coming drivers.

A new, haute couture Custom Club Coupe by Hayes wore the new styling best. The Club Coupe featured enlarged side glass, narrow door pillars, and a unique roofline distinguished by a two-piece rear window and a central character line.

Price for the Custom Club Coupe was a lofty $1,145, and production was just 264 cars.

Engineering had not been neglected. New for 1939 was "Handy-Shift", a gear shift lever mounted on the steering column, which controlled a "Syncro-Silent" three-speed transmission with optional overdrive. Moving engine parts now had "Superfinish" which increased part life, improved efficency, and reduced oil consumption.

More light-hearted advances were the "Safety Signal" speedomater that changed color with speed, and the adjustable front seat that raised while it moved forward.

The 1939 was well received. 54,449 were built.

Beautiful waterfall grills - 1941

In 1941, DeSoto found the styling hallmark that would define the make for all time. New "Rocket" bodies wore beautiful waterfall grills. The frontal theme would remain a DeSoto trademark through 1955. Indeed, it would be the toothy DeSoto grins of the early Fifties that motorists would recall most fondly.

1941 also brought an engineering feature famously associated with DeSoto, the semi-automatic transmission. New to the options list was Simplimatic, DeSoto's version of a four speed transmission shared with Chrysler. DeSoto promotions happily informed prospective customers there was "no need to shift or use the clutch, You're in a new DeSoto!" Simplimatic came close to a true automatic in driver operation. Close enough, in fact, that DeSoto used the transmission with minor improvements through 1953.

To get underway, the driver used the clutch to shift the gear lever into "high." Then, he merely pressed the accelerator. If conditions permitted, the driver eased his foot from the gas around 14m.p.h. allowing Simplimatic to shift from 3rd to 4th. Coming to a light, Simplimatic shifted back down independently and the Fluid Drive coupling made sure there was no stalling and no need to clutch. As DeSoto stressed, the operation could be performed hundreds of times with a minimum of effort.

If a Simplimatic DeSoto owner wished to make a quick get away, he used the clutch to place the lever in "low." Stomping the accelerator produced substantial engine noise and tire spin, which continued as long as the operator could bear. He then lifted his foot and let Simplimatic shift from first to second. To cruise comfortably, the clutch was pressed in and the lever returned to "high" where an alert Simplimatic was automatically in fourth gear. If another car was threatening to pass at a monstrous 40 mph, Simplimatic could be kicked into passing gear with a jab of the accelerator. The 100 hp six, however, would be exhausted at 90 mph.

The appeal of Simplimatic and DeSoto's new smile surely helped production reach the 99,999 cars built. One wonders what held back that extra DeSoto to make it an even 100,000.

The end of civilian car production was in sight when the New Yorker's "Motors and Motoring" column praised DeSoto's new 1942 Airfoil headlamp covers. The entire frontal treatment, including low-lying, waterfall grill, was described as having "a solid well-knit look." The magazine also pointed out Chrysler Corporation's whitewall trim rings offered in lieu of increasingly hard to find white wall tires.

Matters of style such as these became insignificant after December 7th. Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and the United States went to war.

A conquistador at heart, DeSoto enthusiastically joined the war effort. DeSoto factories put civilian production aside February 9 and commenced building Sherman tank parts, Martin B-26 Marauder fuselage sections, B-29 Superfortress nose sections, Navy Helldiver wing sections, and Bofor anti-aircraft gun parts. On the home front, a '42 DeSoto toured the country selling war bonds.

8 out of 10 want DeSoto again

When civilian automobile production resumed late in 1945, customers returned the favor of DeSoto's patriotism by flocking to its show rooms. "Demand," said DeSoto, "is so great that in spite of all our efforts some delay may be necessary before your dealer can make delivery to you."

Material shortages and labor strife contributed to DeSoto's inability to fill orders. However, it was true that a segment of car starved America didn't just want new cars, it wanted new DeSotos. 1946 DeSoto promotions joyfully bragged "8 out of 10 want DeSoto again." The boast was based on a survey of 1941 and 1942 DeSoto owners.

Demand peaked with the 1950 DeSoto.

1950 DeSotos were handsome machines with wide chromium grins and strong correct lines. They were huge cars, bigger than Mercurys, Pontiacs, Oldsmobile 88s, Buick Supers, and the Packard Eights. There was even a new model to strut DeSoto's many virtues, the Custom Sportsman hardtop coupe.

Hardtops are virtually unknown today, but they were a profitable phenomenon during the fifties. By definition, a hardtop is a car with a steel top in the manner of a sedan, but lacking door posts. They were, in essence, convertibles with non-retractable solid tops. The body style provided a better view from the inside and made even the biggest American cars appear sportier on the outside.

Like General Motors' hardtops, DeSoto's Sportsman delivered a special look. Its wrap around rear window and "V" shaped rear roof pillars created a care-free character that had previously been found only in DeSoto convertibles. The Sportsman also came standard with wide whitewall tires, full wheel covers, and exclusive interior details.

DeSoto's Sportsman shared many curious characteristics with other Custom models. For instance, the majestic bust of Hernando deSoto on the hood could be fitted with a carefully detailed plastic face. Behind Hernando's stern expression was a small bulb that illuminated the Spaniard whenever dash lights and headlights or parking lights were turned on. The dash lights themselves were unusual. Concealed bulbs in dark glass spheres set the control panel's pale green numerals aglow with an unearthly purple glimmer.

Aside from its premier pillarless car, DeSoto's other 1950 talking points were roomy interiors with chair high seats and DeSoto's smooth ride. One advertisement showed an enthusiastic DeSoto passenger asking the proud driver, "New road?" To which was replied, "No, new DeSoto!"

Sales rocketed 42% over 1949 and production reached a record setting high of 133,854. Never had DeSoto moved so many cars during a model year. Unbeknownst to DeSoto, it never would again. DeSoto sailed into a doldrums from which even the new 1952 FireDome V8 couldn't rescue it.

FireDome, a sparkling, hemi-head V8 powering a new carline by the same name

During the late Forties and early Fifties, new V-eight engines from Cadillac, Chrysler and Oldsmobile were at the forefront of an emerging horsepower race. Large family cars with inline sixes, like DeSoto, were becoming passe.

DeSoto answered the challenge with FireDome, a sparkling, hemi-head V8 powering a new carline by the same name.

FireDome eclipsed its bigger Chrysler Firepower brother by delivering more road horsepower per cubic inch displacement than any other motor. FireDome cut four seconds from the time last year's DeSoto needed to travel from 0-60. Top speed was increased to 100mph.

What astonished everyone was how effortlessly FireDome produced its 160 hp at 4,400 rpm. The 1952 Oldsmobile Supper 88 V8, considered by many of the day to be a paradigm of performance, required 303 cubic inches, 7.5:1 compression, a four barrel carburetor and premium gasoline to make 160 horsepower. The DeSoto FireDome needed only 276.1 cubic inches, 7.0:1 compression, a two barrel carburetor, and regular gasoline for the same 160hp. In addition, FireDome's hemi-head limited pinging and resisted power robbing combustion chamber deposits.

DeSoto was overly modest about the FireDome. One 1952 DeSoto television advertisement chose not to mention the V8. Instead, the commercial pictured a stark, black, six cylinder DeSoto sedan that the announcer described as having chair high seats, plenty of interior room, and a smooth ride thanks to Oriflow shock absorbers. A happy family piled into the DeSoto and rode away smiling.

Regardless of the 45,830 DeSoto FireDomes that were built, overall DeSoto production had fallen from a disappointing 106,000 (est) in 1951, to an abysmal 88,000 (est) in 1952. That same year, Chrysler Corporation was overtaken by Ford as the country's second most prolific auto maker. Labor problems and war production priorities were partly to blame.

The restyled 1953 DeSotos were the kind of DeSotos people remember best. They were big, covered with chrome, and extraordinarily plush. "Motor Trend" magazine wrote a glowing road report about the 1953 FireDome sedan. The six passenger car was described as "a desirable family car" and powered by an engine with "high performance characteristics."

"Motor Trend" hurled its 4,120 pound FireDome from 0-60 in 15.5 seconds, nearly 5 seconds faster than the similarly priced Kaiser Manhattan tested in the same issue. Of course, the 600 pound lighter Kaiser was hindered by its 118hp six. Performance enthusiasts wondered what DeSoto's V8 would be capable of in a lighter, more aerodynamic body.

DeSoto gave a strong hint with a two-door show car called Adventurer.

1955 Advanced Styling

DeSoto suddenly changed in 1955; so much so even Betty Grable was forced to stop and stare. She and husband Harry James, with Groucho Marx hiding in the back seat, appeared on national television extolling the virtues of the “Styled for Tomorrow” 1955 DeSoto. “Jumping Citations!” exclaimed horse enthusiast Harry at his first glance. “It ought to be great in the stretch. I know a thoroughbred when I see one.” Betty agreed, and explained to her husband that the new top-line Fireflite's V8 was the equivalent of 200 Native Dancers.

DeSoto had power styling to go with its hemi power. DeSoto was longer, wider, and sleeker than any previously. It was also more colorful. DeSoto Fireflites and Firedomes could be dressed up with enormous, fang-shaped color panels that were standard on the Fireflite convertible and hardtop. DeSoto even introduced one of the earliest three tone paint jobs on the 1955 Coronado spring special. The loaded $3,151 sedan was resplendent in white, turquoise, and black.

DeSoto was equally new on the inside. PowerFlite automatic was operated by an intriguing Flite-Control lever mounted on the dashboard. The dashboard was dramatically styled with a dual cockpit gull wing theme. Even the view out was improved with DeSoto's first wrap around windshield.

Riding in a 1955 DeSoto was an experience. The engine was whisper quite and the ride extra smooth. There seemed to be miles between the driver and front seat passenger. Everywhere, there was quality whether it was the Fireflite Sportsman's leather upholstery or the Firedome's glossy dashboard. A '55 DeSoto was sure to please even the most jaded consumer.

Of course, sales were high. 114,765 DeSotos found happy owners for the 1955 model year. The calendar year total of 131,753 was the best since 1946.

Then something curious happened. The auto industry experienced a significant downturn in 1956. Oldsmobile lost over 97,000 sales, Buick more than 100,000 and Pontiac nearly 150,000. At Chrysler Corporation, Dodge sales eased by 36,000 cars and Chrysler sales by 24,000. DeSoto, however, built nearly as many cars in 1956 as it had in 1955. Model year production totaled 110,418, only 4,347 cars fewer than 1955. To top it off, more DeSotos than Chryslers were registered that year and DeSoto climbed to 11th place in the industry. Regardless, five years later DeSoto would be canceled.

The dynamics of DeSoto's demise were already in motion. Top management at Chrysler Corporation suggested Chrysler Division drop its bottom line Windsor to allow more room for DeSoto. Chrysler Division protested. Since 1946, Chrysler had fostered its low end products, and by 1956 had two-thirds of its volume provided by Windsor. Besides, Chrysler no longer had the option of moving up-market. The majestic Imperial was set off as a separate make in 1955 to compete with Cadillac and Lincoln. Having put itself in a difficult place, Chrysler would make no concession to DeSoto.

In 1956, DeSoto didn't need Chrysler's charity. The line was DeSoto's most formidable ever with new tailfin styling, DeSoto's first four door hardtop, and a fiery high performance two-door called Adventurer.

Like a brilliant avenging angle with her wings out stretched, the golden Adventurer stormed into the horsepower race. The finned hardtop colossus scorched Daytona Beach at 137 miles per hour, and surged through Chrysler's Chelsea Proving Grounds banked oval at 144 miles per hour. It even leapt the height of Pike's Peak serving as pace car for the year's competition climb. Nothing from the opposition, not the Thunderbird, Corvette, or Studebaker's Golden Hawk, could match the Adventurer's enormous power and high top speed.

Adventurer's motivation was an enlarged DeSoto hemi sized at 341.4 cubic inches. Horsepower was rated at 320, which was more than any other engine offered in DeSoto's price class.

Adventurer achieved its stunning performance without sacrificing luxury. Standard equipment included push button control Powerflite automatic, power steering, power seat, power windows, power brakes, windshield washers and electric clock. On top of these, the Adventurer delivered a custom interior with padded dash, dual rear view mirrors and dual radio antennas atop the fins.

As was true with legions of DeSotos before it, the Adventurer was a lot of car for the money. It came with more glitter, more features, comparable performance, and a marginally better power to weight ratio than the base Chrysler 300. Yet, the DeSoto cost $567 less. In six weeks following the Adventurer's February 18 introduction, all 996 examples built sold at $3,678 apiece.

In a rare extroverted moment, DeSoto flaunted its many virtues by pacing the 1956 Indianapolis 500. The DeSoto chosen for the duty was a shimmering gold and white Fireflite convertible decorated with Adventurer trim. While most onlookers mistook the modified Fireflite to be an Adventurer convertible, they couldn't mistake the brand. "DeSoto" was painted on the doors in large block letters and signs on the raceway proudly declared "DeSoto Sets the Pace."

DeSoto's slogan was no joke. The DeSoto pace car was a fire-breather equipped with the Adventurer's engine. With DeSoto Division president L. Irving Woolson at the wheel, the DeSoto pace car broke all previous pace car lap speed records. The convertible was doing better than 100 miles per hour when it left the racers.

The exotic Adventurer aside, the DeSoto Fireflite came with more standard horsepower than most cars in its category. At 255hp., the Fireflite V8 was more robust than anything from Mercury, Oldsmobile, or Pontiac, and equal to Buick's biggest engine. Zero to 60 took an effortless 10.9 seconds and the top speed was 110 miles per hour.

Back in the fifties, automotive evolution progressed at a frantic pace with car manufactures bringing out new models every two or three years. DeSoto was due for something new in 1957, but no one could have predicted how new the 1957 DeSotos turned out to be.

"It's DELOVELY! It's DYNAMIC! It's DeSOTO!"

1957 DeSoto television commercials merrily sang, "The most exciting car today is now delighting the far highway. It's DELOVELY! It's DYNAMIC! It's DeSOTO!" The jingle didn't exaggerate. The 1957 DeSotos were amazing cars, perfect for the space age.

In fact, the new DeSoto had every appearance of being able to fly. Huge tail fins soared majestically from the rear fenders and terminated at a set of triple lens rocket launcher taillights. An illusion of jet propulsion was created by dual oval exhaust ports in the back bumper. On cold mornings, DeSotos left convincing vapor trails.

Credit for DeSoto's appearance goes to Virgil Exner, Chrysler Corporation's head stylist and perhaps the post war era's most gifted designer.

Unlike other cars of the day, the 1957 DeSotos were slim. They were fascinating visions of an aerodynamic future. The fins actually served a purpose. They increased stability at high speed and reduced the effects of wind buffeting.

Stability was more important than ever, for beneath the 1957 Adventurer's sleek new hood was America's first standard equipment engine producing one horse power for every cubic inch of displacement. Three hundred and forty-five horses bolted from 345 cubic inches at 5,200 rpm.

Those horses were harnessed to Chrysler Corporation's new TorqueFlite three speed automatic transmission. Though the unit was among the best in smoothness of operation and efficiency, it was the futuristic push-button controls that kept America talking. It seemed almost insignificant that DeSotos also came with Torsion-Aire torsion bar front suspension - a giant leap forward in riding comfort and handling.

The 1957 DeSoto line was the biggest in the make's then-28 year history. The DeSoto Adventurer became available as a convertible as well as a hardtop. Station wagons appeared in the Fireflite series. A new Firesweep nameplate was added at the bottom of the DeSoto price ladder. Firesweep offered three cars costing less than $3,000 in addition to DeSoto's least expensive wagons.

DeSoto's triple punch of styling, performance, and price made 1957 a memorable model year. As sales at Buick, Oldsmobile and Pontiac plummeted, DeSoto gained by 7,096 units. 117,514 DeSotos were built for the model year.

1957 was a good time for DeSoto. It was also a tragedy. Corporation-wide quality problems resulted in some horribly built cars. It's said that DeSoto four door hardtops built at Los Angeles leaked so badly in the rain that occupants were wise to exit the car to avoid drowning. One 1957 DeSoto Adventurer was incapacitated for four of the total 18 months it was owned by its first owner. The car went through four transmissions, three power steering units, two new double point distributors, new valve guides and a new radiator. Reportedly, it took considerable effort and the attention of Chrysler's Chairman of the Board to have the car corrected.

Stories like these and a propensity for early rust angered DeSoto's traditional clientele. DeSoto had always been a well-built car until 1957. Worse, those who had never bought a DeSoto before resented the car's inability to live up to appearances.

Quality control was a problem throughout Detroit in the late fifties. However, the sin seemed greater at DeSoto in light of the make's previous high standards.

Predictably, customers didn't return to DeSoto show rooms for 1958. Making matters worse was a recession. Unemployment topped 5.1 million meaning fewer people could afford a new DeSoto. Indeed, better mid-priced cars were sorely hit. General Motor's B-O-P trio declined for the third straight year. The new Edsel, Ford Motor Company's naive foray into Dodge and Pontiac's territory, met a cold 63,000 unit reception amidst enormous publicity. Mercury too declined. Hudson and Nash were gone altogether.

DeSoto delivered an improved product that year. The cars were consistently better built. A lighter weight, less expensive wedge-head V8 replaced the heavy, complicated hemi. Performance increased. A DeSoto Firedome with the optional 305hp, 361 cubic inch V8 flew from zero to sixty in 7.7 seconds. Top speed was 115 miles per hour.

Ironically, as DeSoto struggled to regain buyers, the high profile Adventurer embarrassed itself with an engineering blunder. For $637.20, performance enthusiasts could boost the Adventurer's 345 hp to 355 hp via Bendix electronic fuel injection. Though futuristic, the system proved nearly inoperable and most all Bendix EFI cars were recalled and fitted with dual four barrel carburetors. The unfortunate occurrence gave ammunition to those who found the wedge-head engine an inadequate successor to the hemi.

As DeSoto production dived nearly 70%, Chrysler Corporation panicked. DeSoto was unceremoniously yanked from the Wyoming Ave. assembly plant it had occupied since 1936. From July 1958 forward, senior DeSotos would be built alongside Chryslers on Jefferson Ave.

If management was ready to write off DeSoto, the styling department wasn't. In May of 1959, a radical prototype emerged from Virgil Exner's "back room" studio. It was a convertible with an aggressive new interpretation of the Forward Look. The hood was noticeably longer than the trunk and accentuated by menacing fender blades. It had no fins, but rather sculpted quarter panels and a smooth sloping trunk. Significantly, the nameplate on the hood proudly read "DeSoto." The concept was dubbed the S-series and approved for the coming 1962 model year change. Chrysler's other brands were instructed to take their inspiration from the new DeSoto.

Meanwhile, DeSoto offered its most flamboyant cars ever. 1959 Firesweeps, Firedomes, and Fireflites were available in any of twenty-six solid colors or 190 two-tone combinations. All DeSotos wore a triple air scoop front bumper along with a fine mesh grill. The Adventurer, complete with gold sweep spears and chrome streaks on the trunk lid, provided swiveling front seats to make entry and exit from the low ridding performance car easier.

For all the glitter, 1959 was a dubious year production wise. Almost 6,000 more DeSotos were built for the calendar year, but model year production fell again. At 45,724 cars, DeSoto was one of only two manufacturers to score lower sales in 1959 than in 1958. Simultaneously, DeSoto celebrated its thirtieth anniversary and built the two-millionth DeSoto.

DeSoto production came to a halt November 30, 1960

The 1960 DeSoto line-up told the tale.

The Firesweep and venerable Firedome lines were dropped. Station wagons and convertibles disappeared. The once glamorous limited edition Adventurer was demoted to Fireflite status. Fireflite in turn was pushed down to replace Firedome.

Although they were few, the 1960 DeSotos were good. Both Fireflite and Adventurer boasted Chrysler Corporation's new Unibody construction. Along with Unibody came sounder build quality and an elaborate seven step rust proofing process. Drivetrains remained exemplary.

Newly optional was a Ram Charge V8. The 383 cid motor utilized twin four barrel carburetors perched atop ram induction tubes. The tubes accelerated intake velocity at certain R.P.M. creating a turbo-like horsepower boost. The induction system was matched by dual exhausts. DeSoto thoughtfully provided 12 inch brakes.

The Ram Charge option was available only on the Adventurer, which already delivered 305hp. Fireflite customers had to be content with 295 hp.

At the corporate level, scandal hinted at the mismanagement that debilitated DeSoto. William C. Newberg, who had been with Chrysler for nearly 30 years, became president of Chrysler Corporation April 28, 1960 when L. L. "Tex" Colbert stepped down. That June, Colbert's carefully groomed successor was fired by Chrysler's Board of Directors. It was alleged Newberg had a conflict of interest at Chrysler, namely financial holdings in companies which supplied Chrysler Corporation. Newberg's removal was followed by other resignations and a year-long battle.

The primary victim was DeSoto. As Chrysler collapsed on itself, the stunning S-series DeSoto prototype and its Chrysler offshoots were canceled. Suddenly, DeSoto had no future.

Sales of the 1960 models were understandably low. Chrysler Corporation had done everything possible to weaken DeSoto's position. For the 1960 model year, 25,581 were built. It was the worst model year since 1934, but it wasn't the last. Half-heartedly, a 1961 DeSoto was introduced October 14, 1960. Set up to fail, it was the last DeSoto.

The 1961 model wasn't granted the courtesy of a model name. It was simply dubbed DeSoto. What buyers existed were given a choice of only two body styles - a two door hardtop and a four door hardtop. Both wore full length chrome spears along their sides and shared a uniquely styled front end. They held little visual link to past DeSotos though the name was prominently displayed in the upper secondary grille and along the trunk lid.

Like the 1960 model before it, the last DeSoto used a 122 inch wheel base, the same span used by full size Dodges. The dashboard, with its three tier design and raised speedometer, could be traced back to Dodge. Even the engine, with an uninspiring 265 horses, came from DeSoto's less prestigious sibling. The days of lanky 126 inch wheelbases and sparkling performance were clearly over.

In its oddly beautiful 1961 dealer brochure, DeSoto made one final, rambling plea:

For 1961, DeSoto proudly presents a fine new car. It is a car rich in traditional DeSoto quality, fresh in the way it looks and performs. It puts into your hands the most all-around value in its price class. The 1961 DeSoto is not a former middle priced car scaled down in any way to attract the mass of low priced car buyers. Nor is it for those who are willing to pay a premium for a status symbol. Rather, the 1961 DeSoto has been deliberately designed for a particular kind of person who appreciates the additional roominess, the distinctive refinements and the reassuring "feel" of an automobile in DeSoto's class. It offers all these things, in superior measure, at a price you will find surprisingly low. Surely, the 1961 DeSoto has much to offer you. In this brochure, you will find some of the reasons you should look into this new car. Your Plymouth-DeSoto dealer will show you many more.

Then there was silence.

After 32 years, DeSoto production came to a halt November 30, 1960. Dealers were notified by telegram.

Available De Havilland Aircraft Company Ads by date and category:

1900 - 1919 |

1940 - 1949 |

1970 - 1979 |

|

|

|

1920 - 1929 |

1950 - 1959 |

1980 - 1989 |

|

|

|

1930 - 1939 |

1960 - 1969 |

1990 - 1999 |

|

|

|

|

Size - A

Grading - B

Availability - C

Price - $

Shipping and handling - verify postal code

|

|

Size - A

Grading - B

Availability - C

Price - $

Shipping and handling - verify postal code

|

|